Egyptian Science

The ancient Egyptians are famous for many scientific achievements:

- metal working, including working with copper and gold:

- glass-blowing:

- knowledge of anatomy and medicine;

- invention of a calendar;

- the standardisation of measurement;

- paper-making from papyrus reeds;

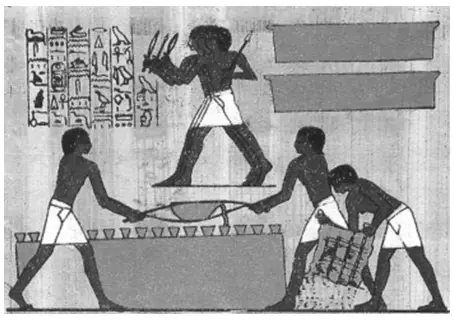

Metal working

The ancient Egyptians learned how to heat metal ores in order to extract the metals. They were skilled metal-workers, particularly in copper and in gold. The picture below shows workmen pouring molten (gold made liquid through heating) into moulds.

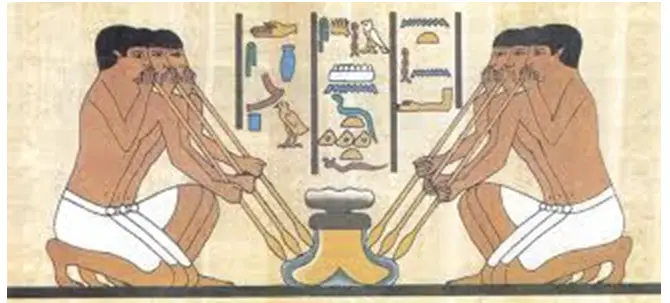

Glass-blowing

The ancient Egyptians may have been the first people to learn how to make glass. They learnt how to heat sand in a very hot furnace and then blow the molten sand into glass. They made glass jars and glass beads. The pictures below show an ancient Egyptian glass jar and a wall painting of workmen blowing glass in a furnace.

Knowledge of anatomy and medicine

The Egyptians knew about the anatomy of the human body. They were able to remove the organs of the body, such as the heart and liver and intestine after a person had died without needing to cut the body completely open.

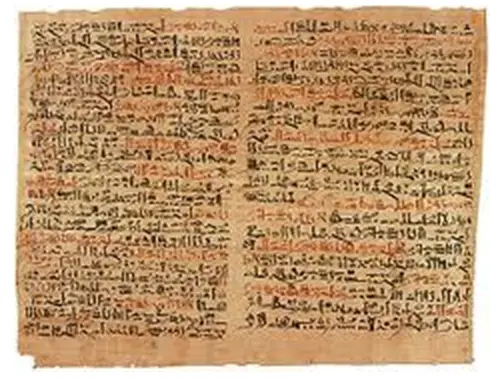

There is a papyrus dating from 1600 B.C. in which the different organs of the body are identified. (It is known as the Edwin Smith papyrus after the man who deciphered it (worked out what it meant).) The papyrus also explains that blood is pumped round the body from the heart (this knowledge was lost and not rediscovered for another 2000 years).

The calendar

Egyptian scientists observed the movement of the stars across the sky. They realised that the annual flood of the Nile happened at the same time as a particular pattern of stars.

From very detailed records year after year they were able to work out that this constellation of stars was in exactly the same place after 365¼ days. The ancient Egyptians gave us our calendar year. This allowed them to forecast when to expect the flood each year.

The standardisation of measurement

The Egyptians were very quick to understand that units of measurement needed to be standardized.

The easiest way to measure something is to compare to some part of your own body. In early civilisations the units of length were defined as parts of the body. The Egyptian cubit, therefore, was the length of the forearm, from the elbow to the fingertips. Other measurements of length could be the hand, the pace or the double pace, the full length of both arms outstretched, or the breadth of the forefinger.

Weight could also be measured in terms of a container. Before measurements were standardised you might buy a basket of corn, or even a boatload.

The Egyptians understood that these measurements could vary. One person’s forearm is likely to be shorter or longer than another person’s. Also the measurements were not related to each other. A basket of corn is not a 100th part of a boatload of corn. A forearm is not twice the length of a pace.

So the ancient Egyptians ‘standardised the units. The Egyptian cubit was now the length of a certain bar of metal, or sometimes wood, which was kept carefully in the royal palace or temple.

Once the Egyptians had standardised the cubit, they based all other measurements on it, so that every measurement was either a fraction or a multiple of a cubit. The Egyptian measurement of area, the ‘setat’ was defined by a square with sides 100 cubits long.

Paper-making from papyrus reeds

Papyrus is a reed that grows in the swamps of the Nile delta (the delta is where the Nile divides into several channels before joining the Mediterranean). The Egyptians were the first people in the world to understand that this reed could be harvested and made into a material on which people could write.

Below is a photograph of the Edwin Smith papyrus from 1600 B.C. (see anatomy and medicine above). This is written in hieratic script (see Egyptian Writing).

Surveying

The ancient Egyptians achieved wonders in surveying from building the pyramids (see Egyptian architecture) to accurate measurement of perfectly rectangular fields.

They used:

- a sighting instrument called a merchet, through which the surveyor looked at a fixed vertical line in the distance;

- a plumb line, which is a line with a heavy weight on the bottom; a plumb line hangs in a perfect vertical line;

- a measuring rope which was tightly stretched between two points; a new measuring rope was stretched and treated with beeswax and resin so that it kept the same length;

- a groma, an instrument that showed a perfect right-angle, used for laying out fields.

Useful Websites

- Great Information here – Website

- Smithsonian website – Mummy Science